Sinai Moon

CHAPTER 3

“Not the worst job in the world.” A languid sea breeze tousled Conal’s fine tawny hair under a sunny Dalmatian sky. I raised my glass of prošek, the sweet local wine, in agreement.

We were on the island of Hvar in the sea between Italy and mainland Croatia. The island’s largest town was a crescent-shaped city of white stone buildings with red-tile roofs hugging a sapphire bay. Above the town stood an imposing Spanish-style fortress atop a rugged pine tree hill. Scents of heather and rosemary drifted on the breeze. No motorized vehicles were allowed in the historic city center, leaving its stone-paved plazas ethereally peaceful.

Conal had chosen an outdoor café on a marble terrace with a view of boats bobbing on the calm blue waters. He looked at me. “So? Any new thoughts?”

I set my glass down and leaned back. “A big reason I wanted to write was to make a difference. And a big reason I’m depressed, I think, is that I’m realizing how little of a difference I’ve made with my writing. So maybe I can use this to make a difference.” I held up the bracelet.

“Great. How?”

“By sending aid to places that need it, for starters. Money or food.”

Conal nodded thoughtfully. “I was in Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya a few years back. I saw a lot of good intentions and a lot of unintended consequences. How much experience do you have?”

“None. I’d have to study it, of course.”

He pursed his lips. “I can tell you right now, plenty of people with PhDs and years of field experience have done more harm than good. It’s noble to want to help, but if you don’t know what you’re doing, it’s depressingly easy muck things up worse. Not to mention people will wonder how you’re paying for massive aid. What will you tell them?”

I exhaled, frustrated. “I don’t know. I haven’t even worked out what to tell my mom. She thinks I’m here on a freelance gig.”

“It’ll be that much harder to keep this a secret if you’re making grand gestures. And you know what’ll happen if anyone finds out.”

“I know.” I looked down, feeling defeated. “So where does that leave me?”

“It seems to leave you as one person with a terrifying amount of freedom.”

* * *

The next morning, after enjoying a leisurely swim in the clear waters of the harbor while Conal investigated a local scuba club, I found the marble terrace café again and ordered a bijela kava (white coffee), Croatia’s version of a latte. I looked around to make sure no one was watching, held my over-sized tote bag under the table, and wished for it to contain several books by my favorite authors: Henry David Thoreau, Rainer Maria Rilke, Carl Jung, Khalil Gibran, Simone de Beauvoir, Hermann Hesse, Lao Tzu, Walt Whitman.

Some time later a stray sunbeam fell across my eyes at a steep angle, and I realized with a start how many hours must have passed. I shoved the literature into my bag, wished it into oblivion, and dashed toward the restaurant Conal had chosen for dinner. The city was labyrinthine, with carved stone steps leading up narrow alleys sprinkled with bursts of brilliant pink and white bougainvillea. By the time I found Conal on the restaurant’s veranda munching on bread and olive oil, I was twenty minutes late.

“Sorry,” I said, out of breath, and plopped down on the seat opposite him.

“No worries. How was your day?”

“Not bad. I spent most of it calling on the wisdom of the ages.”

“Did you actually wish Plato back into existence?”

I laughed. “I suppose books do that in a way.”

“Right. Any luck?”

“It’s a comfort, actually. It’s hard to imagine a world where my favorite writers never put pen to paper.” The terrace was made of pale stone worn smooth with age. At each table a ceramic vase with sprigs of lavender perfumed the air. We were further into the city but also higher up, and the veranda had an expansive view. The still sea reflected massive pink and lilac clouds as the sun sank below the horizen. The barest sliver of crescent moon sank with it.

“That’s another reason I wanted to be a writer. To try to pay it forward, even if only a little.”

“That’s a nice way to put it.”

I smiled tersely. “But I’m not sure anymore. I’m not sure I have anything to add. Maybe the best stuff has already been written.”

“I’m sure Rilke said the same thing to himself.”

“Yeah, and a hundred other poets of his time said the same thing to themselves, and they were right.”

Conal choked slightly on his wine. “I suppose you have a point.”

I sighed. “I did it, you know, I ‘followed my heart.’ Most people only talk about it. I actually did it. And look where it got me.” He opened his mouth to object, but I cut him off. “I worked my way up to this great education that I always dreamed of, then I chucked it all, thinking I might be the next George Orwell. It was ridiculous.”

He patted my hand. “You’ve only been at this for ten years, love. Some people don’t break out for decades. Some never do at all. But if you have to write, you write.”

“I’m not sure anymore that I have to. But then I think about quitting and doing something else and… it’s like I can’t breathe. I had this image of starting my third book with a comfortable advance and fans excited about what came next. I know that doesn’t happen for everyone, but… I really believed that if I visualized it, worked for it, put everything I had into it, I couldn’t fail.” I scoffed. “Magical thinking is what it was. The simple fact is, I gambled ten years and lost. Ten prime years that should have been building up to something. Whatever I do now, I’m starting from zero.”

“Most people your age did whatever was expected of them,” Conal said, “and will keep doing so until they die. They got the ‘right’ job and had kids at the ‘right’ time and never thought another thing about it.”

“Maybe they were on to something.”

“Maybe, but that’s not you. You’re a published author and world traveler. I mean, think about Thoreau. I know he’s a favorite of yours. He went to Harvard, but he didn’t want to do what all the other Harvard grads did. He wasn’t interested. He tutored kids for a while, hung out with philosophers, networked with literary types in New York, and got nowhere. He worked at his father’s pencil-making business until a friend told him to get serious about his writing. He lived in the woods for a couple of years, and later he ran into a tax collector and refused to pay on principle and went to jail for it. Big deal, right? He was a small-town dreamer who barely left Massachusetts and spent years of his life in debt. A lot of people dismissed him as a nobody. But what he wrote inspired Gandhi, Tolstoy, Martin Luther King, and John F. Kennedy.” He sat back and shrugged lightly. “And now they study him at Harvard.”

I couldn’t help but smile. I looked down. “I guess I just don’t seem to have a lot of faith in it anymore. Not for me.” I rested my chin in my hand and picked a lavender blossom out of the centerpiece, crushed it, and inhaled the scent. “I could have been a brain surgeon by now, you know.”

“You could have been a lot of things. But I don’t think you want to be a brain surgeon. And would you want your brain surgeon to be someone who didn’t want to be a brain surgeon?”

I threw crushed remnants of lavender at him. “I could have worked on cold fusion or something.”

“You told me you hated working in a physics lab in college.”

“I could have gotten a PhD. I could have worked my way up to… something. I could have started a business.”

“Darling, you were sick to death of school by the time I met you. You’re not the type who gives a shit about working your way up hierarchies, and you sure as hell don’t care about business.”

I sighed. It was hard to have everything so deeply unsettled, and I hadn’t accomplished what I wanted to, and the path ahead wasn’t any clearer than it had been ten years earlier. But now that I was out of the achievement-centric pressure cooker of New York, my assessment of myself was starting to seem a bit harsh. In New York, you were either a Big Deal or a nobody. The whole thing got into your head after a while.

“Either way, I’m sorry to say it,” Conal went on, “but right now you don’t seem like yourself. You’re a shadow of the woman I knew in Palestine. In Palestine you were more…” He trailed off as if searching for the words.

I nodded, my face reddening. I hated for him to see me like this. But Conal had a way of allowing me space to sit with feelings, however uncomfortable, without judgment. I loved him for that. “I liked myself better then, too. I’m not sure what happened.”

“Maybe you should think about dealing with that,” he said gently, “before you make any major life decisions.”

“How?”

“I’m not sure.” The wind caught his hair, and I watched it flop over and back again.

I looked at the bracelet. “Maybe I could start by trying to think of this as a gift rather than a burden.”

“Sounds like a good place to start.”

We backed off the heavy philosophical discussion and chatted until the food was long gone and we were starting to get drunk on the wine.

“Shall we?” Conal asked. We walked back to the hotel his editors had sprung for. There were two queen beds, and we each chose one and fell into it.

A hazy thought came to the back of my mind: Wouldn’t it be nice if—

But it was chopped off, half finished, by the curtain of sleep.

* * *

Conal was working intensely on his laptop when I awoke, so I slipped out to visit the sauna. For lunch we ambled back to our favorite café and ordered double espressos and omelets with spicy pork sausage and sheep’s milk cheese.

“So I did a little research this morning,” Conal said, “and I found some quotes that might interest you. First, Leo Tolstoy: ‘If you see that some aspect of your society is bad, and you want to improve it, there is only one way to do so: you have to improve people. And in order to improve people, you begin with only one thing: you can become better yourself.’”

I rolled my eyes. “I know, I know.”

“And here’s one by Ramana Maharshi: ‘Wanting to reform the world without discovering one’s true self is like trying to cover the world with leather to avoid the pain of walking on stones and thorns. It is much simpler to wear shoes.’”

I laughed. “OK, OK, you’ve made your point. If I want to change the world, I should probably start with the hot mess you see before you.”

“At least for a time,” he said with some relief. “Honestly, what sense does it make to try to change something as massive and complicated as the world when you don’t even understand yourself?”

The waiter delivered our vodka-pineapple cocktails, and I ran my finger across the perspiration on my glass as I felt my resistance to his idea rise in my chest. It felt selfish to have such an astonishing gift at my disposal only to step back and focus on myself. It sounded like New Age self-indulgence. I was itching to do something, make some kind of difference, after feeling so useless for so long.

But whatever I had learned in the past ten years, I clearly hadn’t managed to find any real, strong, solid footing. As hard as it was to admit, I knew in my heart that Conal’s suggestion made more sense than any blundering save-the-world scheme I could come up with in my polluted state of mind.

I sighed. “Any ideas on how to do that?”

He leaned back and shrugged. “You tell me. What would you most sincerely like to do right now? Don’t judge. Whatever comes to mind.”

I continued staring at my glass. I missed the days when travel was about joy and discovery. I missed myself when I was exploring and just to learn and grow, not worrying about any particular outcome. It seemed like going back to that now would be tantamount to going backwards as well as abdicating some cosmic duty. But I’d completely lost track of what that duty might even be.

“I’ve always wanted to hike in the Alps,” I said softly.

“That sounds lovely,” he said. “Why not? Alps it is. Second question: What’s something you’ll regret never doing if you don’t do it while you’re young and single?”

I glanced up thoughtfully, and a calculating look crossed my face.

“What was that?” he asked. “What were you thinking just then?”

A crazy, inchoate plan was forming in my mind. It was so unlike me, I feared trying to explain it to Conal might kill the idea in its infancy. “Beirut,” was all I said.

He narrowed his eyes but didn’t press. “Amazing city.”

“And some of the most beautiful people in the world.”

Conal smiled a bit sadly. I wondered if he had history with a Lebanese girl. When he and I first met, I was dating a Palestinian who lived forty miles and seven checkpoints away, and Conal had a girlfriend back home in London. It was hard to tell whose relationship was longer-distance. It was only a five-hour flight to London while the trip through the checkpoints could take seven hours or more.

“Moving on, question three,” he said quickly. “Where have you spent time that you felt something peaceful, or where you really felt at home?”

“You know the answer to that,” I said, bringing my leg out from under the table and brandishing my anklet. We both had a reverential love for the Sinai, a remote triangle of mountainous desert wedged between Asia and Africa. It had the feel of its own little world, a Lotus Land of friendly charm and otherworldly beauty.

“Well, there you go,” he said. “The Alps, Beirut, and the Sinai. That’ll keep you occupied for at least a couple of months. Then you can call me and we can figure out where to go from there.”

I took a breath and began to feel the old surge of excitement I used to feel before an adventure with no agenda other than a few points on a map and a hope it might somehow prove enlightening. Here I was again, in my thirties, doing the same thing I always did when I was lost: buying a plane ticket and running away in search of something as ineffable as freedom and beauty and maybe even who I was meant to be.

Would healing my mind do anything to help heal this troubled world? It was probably a fool’s errand, as usual, but I felt a lightness in my chest and looked forward to the days ahead for the first time in ages. That had to be worth something.

But first I had a few things to take care of back home.

###

Thanks so much for reading! I welcome any thoughts or feedback you might be willing to share. More chapters are available to anyone who'd like to read them. Please email me at pamolson at gmail dot com if so.

Contact Me to offer feedback

or read more chapters

|

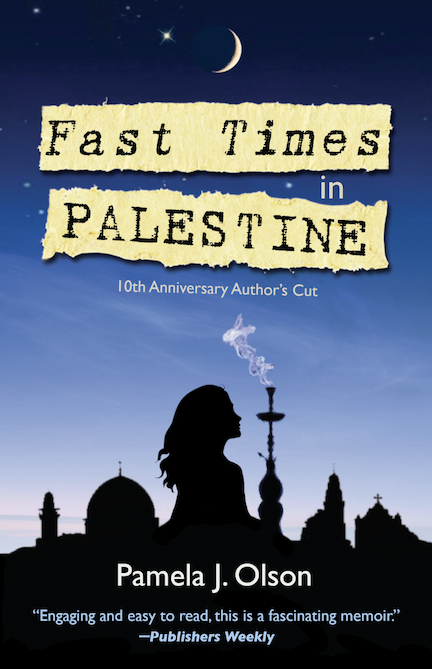

Click to view my first book's

Amazon page

|